Brent Wilson and his former colleagues who joined him after being laid off from an Oklahoma City oil and gas company might be sitting on a gold mine.

A gold mine of lithium, the mineral that’s a hot commodity as the U.S. electric vehicle rapidly expands, creating a strong demand for the creation of the batteries that run the EVs.

“Tip of the spear,” is how Wilson describes his fledgling company.

Or as they say “making lemonade out of lemons.”

Wilson was a geologist with Chesapeake Energy until Chesapeake initiated layoffs in 2017 amidst earthquake activity in Oklahoma. The seismicity was blamed on the recycling of water and that’s what spurred Wilson and his colleagues to consider other uses for the water.

“We started kicking around ideas—what if we could use that water recycling and extract these things out of the water,” he recalled during an interview with OK Energy Today.

With their chemistry background, Wilson and friends knew there was more to the water than oil and gas.

“We were kind of curious about Tesla’s explosive growth with the electric cars,” said Wilson as he explained how they made initial investigations into whether the content of the water could be used for EVs. Management at the time didn’t offer any interest in their findings.

“Dead on arrival” as Wilson put it. Then the layoffs occurred at Chesapeake and Wilson and friends were out of jobs by February 2018.

He finished a Master’s Degree at Oklahoma City University and still wondered about the salt water that was part of the oil and gas industry.

“It was these batteries that really got my attention. I just really felt compelled that this was gonna be something of the future somehow.”

He put some money together and by June 2018, Galvanic Energy was formed.

“Within a couple of months, I hired back my former team members and we started the company from there.”

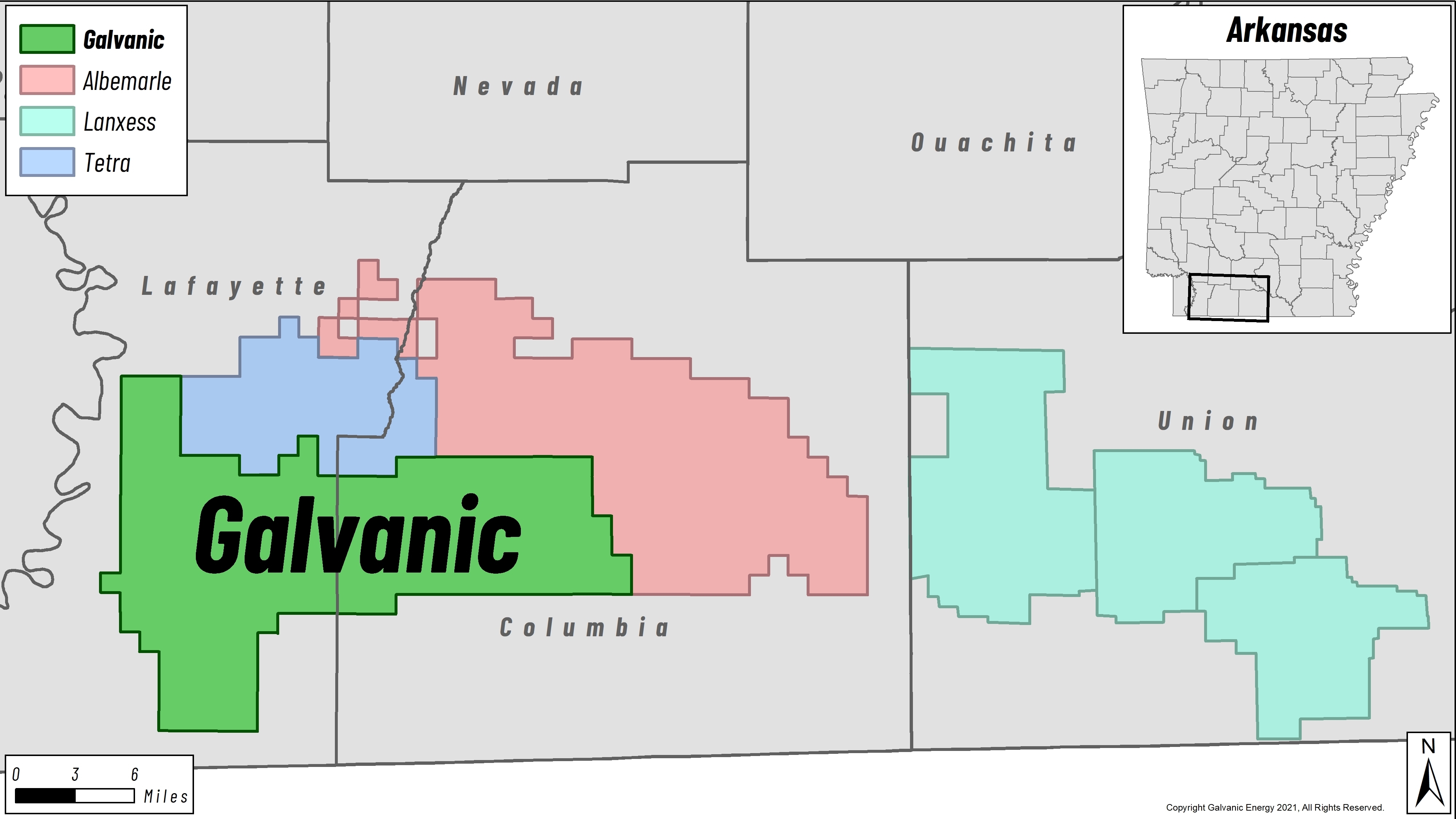

Wilson said he spent a year researching for the best areas where lithium from salt water might be best sourced and settled on Southwest Arkansas. There, the company has leased 120,000 acres for 25 years.

Galvanic’s subsidiary, Saltwerx announced in July it had secured the lithium and bromine leases within Columbia and Lafayette counties.

It is the second largest bromin producing area in the world and the product is from the Smackover formation.

Wilson looks at the layoffs by Chesapeake as “fortuitous” for him and the colleagues who now make up the executive branch of Galvanic Energy, headquartered in Oklahoma City.

Galvanic isn’t a mining company like those attempting to excavate lithium in Nevada. Instead, the company focuses on salt water or brine and that’s where Southwest Arkansas comes into play. It’s an area with a heavy concentration of brine which is a high-concentration solution of salt in the water. It also forms naturally due to evaporation of ground saline water.

Wilson was familiar with salt water. An estimated 80% to 90% of the product from oil and gas exploration is typically salt water.

“Really, it’s about producing the fluid and extracting the elements. Now this is very specific. In this case we only want the lithium.”

Galvanic’s intentions are to use played-out oilfields or plays that no longer are as productive for oil as they once were. The brine will be pumped out, transported to a plant and the water will be returned to the earth.

The same kind of rigs used in exploration for oil and gas would be used in the removal of the brine—rigs that Wilson is quite familiar with. Since the Smackover formation is at about 9,000 feet, the horsepower from the large drilling rigs would be needed to extract the brine.

“The footprint is really small,” he explained as the brine is dehydrated.

“The first thing you have to do is you have to prove out you can produce and maximize the lithium extraction to convert into lithium chloride, but without the contaminants.”

Galvanic is in the process of sending of the extracted water to companies that might be interested in development of processing plants in the field. Studies are underway as the firm is in pre-production.

“We’ve done all of our exploration work. We are not doing any on-site work currently. Right now, we’re evaluating the technologies before we enter into an agreement with a long-term contract.”

Next step is to a pilot project which will involve selection of the technologies and the choice of a firm that would construct a processing plant.

“This would incorporate bringing the plant to the fields for the first time,” said Wilson.

Once the plant is built, a few thousand barrels of brine a day would be pumped from below the surface and eventual production might result in a thousand tons of lithium a year.

A lot of companies are interested according to Wilson and many are in talks with Galvanic.

The company recently completed a $9 million fund-raising effort and now hopes to move beyond pre-production.

Multiple companies are in talks with Galvanic.

“We haven’t settled on the one at this point, but I would say we’re getting close to having that figure out. Hopefully, by the end of this year so that way, we can move forward with the pilot stage sometime in early ’23.”