A plan to build two big nuclear-waste storage facilities in the heart of the most important U.S. oil field is igniting a fight between frackers and the atomic-energy industry according to a report by the Wall Street Journal. One of the proposed sites is 100 miles from Oklahoma.

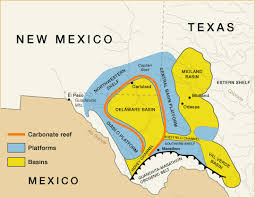

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission is considering proposals to put up to 210,000 tons of nuclear waste—including the most dangerous high-level waste—at two sites in the Permian Basin, the booming oil-and-gas producing region along the Texas-New Mexico border.

The temporary facilities would be surrounded by fracking equipment—shale oil drillers that pump water and sand into the ground at high pressure to break apart rocks and free up oil and gas. One step in the fracking process can lead to earthquakes, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Public officials and oil drillers are fighting a proposal to store high-level nuclear waste at two sites in the Permian Basin.

Stephanie Garcia Richard, New Mexico’s commissioner of public lands, has sent letters to the NRC opposing the facilities, which she said are “smack in the middle” of the oil field. She is joined by oil drillers, who say they are planning to explore for oil around and below the storage site. One of the sites is in a West Texas county that produced 42 million barrels of oil last year.

The NRC is reviewing the proposals and is expected to release results of preliminary environmental studies as early as March. The nuclear waste would be shipped to the locations by train from nuclear reactors all over the country. Together, the sites effectively have enough room to store all the current high-level waste being held at U.S. nuclear power plants.

Finding a place to permanently store waste has been a perennial issue for the nuclear-power industry. Plans for a permanent disposal site in Nevada’s Yucca Mountain, picked by Congress in 1987, have been stalled for years. In lieu of a permanent facility, fuel is currently housed mainly at nuclear facilities.

The Texas site is one of four U.S. locations with a facility for housing low-level nuclear waste, which typically consists of contaminated items like clothing, rags, mops, equipment and tools. High-level waste, which is far more toxic, includes used fuel from nuclear power plants and takes hundreds of thousands of years to decay.

Two companies, Interim Storage Partners and Holtec International, are seeking 40-year licenses to take the spent fuel in what is considered a temporary solution. Interim Storage plans to operate a new facility near the West Texas site while Holtec’s site is over the border in New Mexico.

Interim Storage Partners CEO Jeffrey Isakson says the company’s application takes into consideration the possibility of seismic activity caused by drilling and other impacts from oil and gas production.

“These systems have been designed to withstand extreme seismic events, and have been proven effective over decades of use,” Mr. Isakson said in a statement.

Holtec’s Chief Strategy Officer Joy Russell says its facility was designed to withstand an earthquake that is far more dangerous than the worst earthquake expected over a 10,000-year period.

Because these are considered interim facilities, the waste would be stored on or near the surface. A permanent facility, where spent fuel would be stored 1,000 feet underground, would be preferable, says Charles Forsberg, principal research scientist at the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “You have erosion, you have people, you have wars and all sorts of other things,” he said.

Some worry that if granted, the licenses could be renewed. “These sites may end up storing this waste permanently,” U.S. Senator John Barrasso, a Wyoming Republican said.

Interim Storage Partners is a joint venture of the U.S. division of French company Orano SA and Waste Control Specialists LLC, which was bought in 2018 by private equity firm J.F. Lehman & Company. WCS owns the low-level waste facility in Texas, which would be adjacent to the new high-level facility if plans are approved.

WCS’s site first opened in 2012, just as drillers were starting to use sophisticated hydraulic fracking in the Permian, which turned it into one of the world’s largest producing oil fields. “A decade ago we didn’t have the multistage horizontal fracturing so how could we have anticipated the geological impact of that?” said Ms. Richard, New Mexico’s Commissioner of Public Lands. She also noted the seismic impact of the fracking process that requires reinjecting water into the ground. “The seismic result of the reinjection is unknown,” she said.

The U.S. Geological Survey says the disposal of waste fluid from the fracking process can cause earthquakes. A 2007 report from the International Atomic Energy Agency cautioned that high-level nuclear sites should be single-use and “avoid land with exploitable mineral and energy resources.”

Fasken is worried about the financial impact the nuclear site could have on the land and minerals in the area.