COVID-19 has left the state of New Mexico retreating from its planned heavy government spending based on oil and gas production.

Just witness what the pandemic has done to the state’s rig count. As of last week, there were 51 oil and gas rigs active in the state, according to the latest Baker Hughes count and that was a decline of 5 from the previous week.

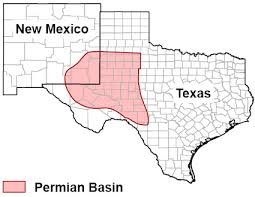

A year ago, New Mexico had 100 rigs drilling mostly in the Permian basin which stretches from West Texas into southeast New Mexico. So did Oklahoma but the Sooner state’s rig count is down to only 9 according to Baker Hughes.

In reviewing the coronavirus impact on the state’s oil and gas industry, Bloomberg reported that the shock waves’s speed and severity is most apparent in New Mexico. Perhaps Bloomberg should have looked at the impact in Oklahoma but it didn’t.

Just months ago, New Mexico, the third-biggest producer of U.S. oil, approved the state’s largest budget ever, paid for by an oil boom that made up 40% of the state’s revenues in 2019. Now that plan has been slashed by more than $600 million, affecting everything from pay raises for state workers to a program designed to provide free community college to state residents.

Oil-producing states across the U.S. are facing a double whammy with both drilling and overall consumer spending cut back by the pandemic. New Mexico, meanwhile, stands as exhibit A of this boom-to-bust dynamic, with the state’s revenue forecasts plunging and more than 4,600 workers in mining, most of which is oil and gas-related, claiming unemployment insurance in the week ended June 13.

“We were just starting to stand on two legs,” said Reilly White, a finance professor at the University of New Mexico. “All of that stuff that passed, and that we were expecting this year, oil was a big part of that. The rug has just been swept out from under us.”

When New Mexico’s legislature initially passed its budget in February, it assumed an average oil price of $50, and continued growth in the state’s part of the Permian Basin. But in the months since, with U.S. lockdowns underway, crude futures fell as low as negative $40 a barrel.

Companies with operations in New Mexico, including Concho Resources Inc., Occidental Petroleum Corp. and Matador Resources Co., have all decreased the number of rigs they plan to run in the state this year. And many producers have also taken the unprecedented step of curtailing significant portions of their existing output.

Prices have returned to the $30 a barrel range since, and that rebound has helped some. But crude and natural gas producers in the state have yet to reboot their output to previous levels, and New Mexico’s Land Office now expects its monthly royalty revenue from the oilfields to drop by half.

On Saturday, the legislature — meeting in a special session — reacted by sending a new pared-down budget plan for Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham to sign.

In the early 2000s, New Mexico’s oil revenue “for the whole year was like $500 million,” said Stephanie Garcia Richard, New Mexico’s land commissioner. This year, though, the Land Office was bringing in about $100 million a month from royalty payments alone. Then the coronavirus hit.

On top of the drop in oil revenue, the state is also contending with a decline in sales tax-receipt revenue as consumers largely stay home amid the shutdowns. But there is a bright side: The past few years of high oil revenue have left New Mexico with a sizable rainy-day fund.

Oilfield activity in New Mexico’s southeastern corner has been steadily increasing for four years. As shale producers drilled through legacy acreage in the Permian’s Midland sub-basin, they moved further west into New Mexico’s Eddy and Lea counties.

Unlike Texas, 90% of production on the New Mexico side of the Permian has taken place on lands owned by the state or federal government. That lets New Mexico’s government collect significant royalties, severance tax and disbursements from drilling. And business was booming.

The regulatory hoops that come with drilling on public lands were a nuisance, but this particular area — known as the Delaware Basin — was hot. And unlike in the last boom, workers were starting to make New Mexico their home base.

“People are moving to these areas, and they’re bringing employees,” Lujan Grisham, the New Mexico governor, said in an August 2019 interview. “I’m seeing long-term investment.”

A Democrat who’s been floated as a potential vice presidential pick, Lujan Grisham sought to capitalize on the boost in revenue by spearheading one of the most aggressive free college proposals in the country.

A version of the plan passed the legislature in February, allocating $17 million to cover tuition and fee assistance to state residents seeking to attend two-year programs at public or tribal colleges. Now, that allocation has been cut by more than 70% to just $5 million, assuming the governor signs the budget she’s been sent.

“Certainly the pandemic has changed everything,” said Tripp Stelnicki, a spokesman for Lujan Grisham, speaking prior to the legislative session. “But amid all the crises the state is managing, the governor is very much committed to making this program work the way it was intended on behalf of New Mexico students and workers and the state’s economy.”

Before the coronavirus, it was easy to see where the money was going to come from. Even as activity on the Texas side of the Permian slowed, the Delaware sub-basin that reaches into New Mexico was going strong.

“It’s been an important revenue source for the state for decades, but with the boom in Permian production, that’s become even more true over the last few years,” according to Daniel Raimi, a senior research associate at Resources for the Future. “Texas is just simply less dependent on oil production revenues. While Texas certainly will experience fiscal challenges, it won’t be as severe.”

Prices Wobble

Now, as prices wobble below the level most producers need to justify new drilling, some leaders say it’s clearer than ever that the state must move its economy away from the booms and busts of the oil industry.

“There’s been a few of us that have argued that we have to diversify our economy and quit being so reliant on oil and gas,” said John Arthur Smith, a New Mexico senator representing the southwestern part of the state. “We’ve lost that argument.”

That was at least part of the motivation behind one of Lujan Grisham’s most ambitious policy proposals since she took office: a move to 100% carbon-free power generation in 25 years.

“Her policies, whether you agree with her or not, were largely designed to diversify those revenue streams, to make New Mexico a more robust economy by focusing on education, by focusing on business development,” said Nicholos Venditti, a portfolio manager for Thornburg Investment Management Inc. in Santa Fe. “The problem with all of those things is they cost money.”

Source: Bloomberg