A lawsuit filed in 2017 by seven landowners challenging an Oklahoma Water Resources Board decision to allow Oklahoma City to draw water out of the Kiamichi River is still alive. A recent filing made several allegations over the OWRB decision according to an article published by the State House of Representatives.

Oklahoma City “treats the Kiamichi River like a checking account for withdrawals, all while keeping Sardis Lake as a savings account, without paying any costs incurred by southeastern Oklahoma.”

That is just one of the assertions made by Norman attorney Kevin R. Kemper in a “brief-in-chief” petition filed in Pushmataha County District Court on 17 January 2019.

A “Water Agreement” inked in August 2016 would allow Oklahoma City to divert up to 115,000 acre-feet of water each year from the Kiamichi River and Sardis Lake. (One acre-foot is equivalent to 325,851 gallons of water.)

That agreement was signed by the chiefs of the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations, then-Gov. Mary Fallin and then-State Attorney General Scott Pruitt, the Oklahoma Water Resources Board, then-Oklahoma City Mayor Mick Cornett, the Oklahoma City Water Utilities Trust, and the Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

The agreement resulted from a lawsuit the Native American tribes filed against the State of Oklahoma and Oklahoma City, a lawsuit that reportedly cost Oklahoma City approximately $2.5 million in legal fees to resolve.

The Oklahoma Water Resources Board approved on 10 October 2017 a permit that would allow Oklahoma City to siphon almost 37.5 billion gallons of water per year from the Kiamichi and Sardis.

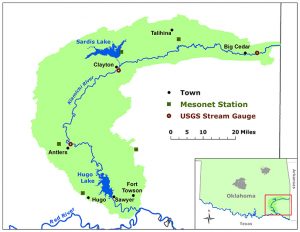

(Sardis Lake is an impoundment of Jackfork Creek, a tributary of the Kiamichi River, which empties into the Red River.)

Kemper represents seven individuals who own land or businesses along the river: Dale Jackson of Clayton; Justin Jackson; Debbie Leo, d/b/a Miller Lake Retreat; Larinda McClellan; Louise A. Redman Trust; Walter Myrl Redman; and Kenneth Roberts, a Tulsa University professor.

Those seven filed suit on 8 November 2017, asking the Pushmataha County court to vacate the OWRB decision or mandate a rehearing “to receive and consider more evidence.”

The petitioners contend that evidence the City of Oklahoma City presented during a hearing on 21-24 August 2017 before OWRB Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) Lyn Martin-Diehl “failed to justify” granting the permit to withdraw water from the Kiamichi River basin.

Oklahoma City and the Water Resources Board had not responded to the petitioners’ latest brief by 26 February 2019, court records indicated.

The allegations include:

Too Many Protesters Were Denied a Voice

OWRB Hearing Examiner Martin-Diehl excluded individuals and entities – in particular, the Kiamichi River Legacy Alliance and Oklahomans for Responsible Water Policy, whose former president is Charlette Hearne of Broken Bow – “who otherwise should have had standing” to protest Oklahoma City’s application.

Consequently, what began as 85 protesters to Oklahoma City’s water-use permit application was winnowed to the seven plaintiffs.

“Each person throughout the Kiamichi River basin who use[s] the river in any way and each association dedicated to the water rights of each person throughout the Kiamichi River basin ought to have standing in this case, were it not for OWRB regulations,” Kemper wrote.

In addition, “impacts upon land, environmental, and economic interests are specific harms that could occur to a party,” he wrote. “Thus, a party has a right to protest a permit application if those harms could occur. Standing belongs to any who would be harmed in any way.”

OWRB’s Order ‘Imperils Ecosystem’ of River Basin

The OWRB’s final order “imperils the fragile ecosystem and residents of the Kiamichi River Basin,” Kemper asserts.

For example, OWRB regulations do not “account fully for the needs of the entire basin’s flora, fauna, humans and economy,” he wrote.

“No one has articulated with precision the exact requirements of the Kiamichi River Basin,” Kemper wrote. The OWRB has not determined: how much water is available from the river, how much water is available for appropriation from Sardis Lake, present or future needs of the region, and whether Oklahoma City’s water withdrawals would interfere with domestic and existing needs.

The state Supreme Court mandated in a previous case that the OWRB could approve an appropriation of water “only if it finds there is surplus water after providing for all prior appropriations,” all riparian domestic uses, all riparian uses approved as reasonable…, “and all anticipated in-basin needs,” Kemper wrote.

Environmental Issues Ignored

Hearing Examiner Martin-Diehl “refused to allow key evidence” at the 2017 hearing “regarding the toll that would be taken” if Oklahoma City’s permit were granted, Kemper wrote. For example, she excluded a letter from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, dated 10 April 2017, which “detailed environmental concerns.”

Martin-Diehl also “failed to take adequate notice of compelling evidence and testimony” from Dr. Caryn Vaughn of the University of Oklahoma, who “has worked extensively” in the Kiamichi River Basin and is “a renowned expert” about freshwater mussels.

The state Supreme Court “mandates the consideration of environmental factors when the OWRB considers a permit application,” Kemper relates in his document.

The Kiamichi River is “known for its high aquatic biodiversity,” Vaughn wrote in 2000. The river is home to more than 86 species of fish and 30 species of freshwater mussels. Mussels provide important habitat and other services for other river organisms, such as insects and fish, Vaughn wrote in 2006.

Beneficial Uses Weren’t Fully Considered

“Beneficial uses of water apply to everyone who applies those beneficial uses,” Kemper wrote in his petitioners’ brief-in-chief.

Beneficial uses include but are not limited to municipal, industrial, agricultural, irrigation, recreation, fish and wildlife, he noted.

In her report to the OWRB, ALJ Martin-Diehl noted that the protestants argued that in “periods of extreme drought,” Oklahoma City’s water withdrawals from the Kiamichi River could result in “decreased aesthetic value of the river, loss of natural aquatic and wildlife … and loss of tourism, an essential element of southeastern Oklahoma’s economy.”

Martin-Diehl wrote that “these and other issues” were not “specifically addressed” in her “Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law,” and the Water Resources Board concluded that “such contentions either are not supported by the law, or are beyond the scope of the Board’s jurisdiction in this proceeding, and therefore should not be considered by the Board.”

When asked why those weren’t valid issues for consideration, the OWRB declined to answer.

Conservation Would Reduce OKC’s Request by One-Third

“If OKC followed conservation plans as outlined in the Oklahoma Comprehensive Water Plan, 2012 Update,” Kemper wrote, OKC “could save at least up to 41,543 acre-feet of water per year,” according to one of the city’s own exhibits introduced during the OWRB hearing in 2017.

Savings of that magnitude would constitute 36% of the entire amount Oklahoma City has requested in its water-use permit application.

Oklahoma City, a water wholesaler and retailer, estimates its per-capita water demand is 180 gallons per day, ALJ Martin-Diehl related in her “Findings of Fact”.

Groundwater Wasn’t Considered by ALJ

Administrative Law Judge Martin-Diehl also wrote in her report that Oklahoma City “has shown that groundwater of good quality is unavailable in the central Oklahoma area from which to draw needed water.”

The OWRB declined to respond when asked whether there was any indication that Oklahoma City performed any kind of detailed research to calculate how much groundwater “of good quality” is available in the central Oklahoma area.

A report prepared in 2012 by Kyle Murray, a hydrogeologist with the Oklahoma Geological Survey, related that the Central Oklahoma aquifer “has an extent of approximately 1.85 million acres (2,890 square miles)” underlying all of Cleveland and Oklahoma counties and parts of Canadian, Kingfisher, Lincoln, Logan, Payne, Pottawatomie, and Seminole counties.

However, the “effective recharge area” of the aquifer is closer to 1.28 million acres, and typical annual precipitation in that area would result in almost 198,800 to 396,500 acre-feet of recharge to the aquifer each year, Murray wrote. That amount would “far exceed the range of estimated groundwater use (26,682 to 46,844 acre-feet)” from the aquifer during the years 1990 to 2005, he pointed out.

Some wells in the Garber-Wellington are tainted with naturally occurring arsenic.

Nevertheless, much of the Central Oklahoma Aquifer is potable. Several municipalities, including Chandler, Del City, Edmond, Guthrie, Midwest City, Nichols Hills, Norman and Shawnee, “draw some portion of their water from the Central Oklahoma aquifer,” Murray wrote in his report.

About 575 wells had been drilled into the Garber and Wellington subterranean formations and were producing 50 to 634 gallons of water per minute, the same document related.

Because fresh water is “readily available” from Sardis Lake and the Kiamichi River, “it is not necessary to consider the availability of groundwater as an alternative source” for the water sought by Oklahoma City, Martin-Diehl wrote.

The OWRB declined to answer when asked why it wasn’t “necessary to consider the availability of groundwater” when evaluating Oklahoma City’s application.

‘Kiamichi Model’ Employed Old Data

The “Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Board Order” prepared by the Oklahoma Water Resources Board’s administrative law judge relied to a great extent on “the Kiamichi Model”.

Kemper urged the court to note that the data for the Kiamichi Basin Hydrologic Model “comes from the 1920s-1970s, well before Sardis Lake was built and started to affect the data downstream.”

Relying on obsolete data “violates Oklahoma law, as the data must have been within FIVE YEARS of the decision in October 2017,” Kemper wrote. “That means primary data for this permit is over 40 years old.”

Requests submitted to the OWRB on three separate occasions (16 and 24 January 2018 and again on 6 February 2019) for information about the Kiamichi Model – “Who developed that model and how? What were the criteria employed in developing the model?” – went unanswered.

A similar request submitted to Oklahoma City on 24 January 2018 was referred to OKC’s Water Trust Attorney, who responded on 26 January 2018, “[T]he permit application referenced by you and the permit, issued by the OWRB, is currently under appeal and is a matter of ongoing litigation. The Municipal Counselor’s Office represents the City of Oklahoma City and does not comment on ongoing litigation.”

Courts Empowered to Determine Property Rights

Kemper argues that the Oklahoma Water Resources Board cannot unilaterally decide who has water rights – because the state Constitution “gives jurisdictional authority to district courts to resolve property issues.”

Stream water is a property right that’s protected by the Constitution, by state statutes, and even by regulations of the Water Resources Board itself, Kemper wrote.

In a case it decided on appeal in 1990, the Oklahoma Supreme Court wrote that “…the common-law riparian right to use stream water, as long as that use is reasonable, has been long recognized in Oklahoma law as a private property right.”

Public Notice of Application was Inadequate

The OWRB failed to provide adequate public notice to property owners in the river basin. The state agency “could have identified and served each and every property owner in the Kiamichi River basin simply by going to the local courthouses and compiling records from the County Clerks,” Kemper wrote.

Instead, the agency relied on legal notices published in one newspaper each in Pushmataha, Choctaw, Latimer, Pittsburg and McCurtain counties in March of 2017.

“To this day, people throughout southeastern Oklahoma keep saying they had not heard about this case until it had been filed,” Kemper claims.

Publishing legal notices in those five newspapers was not sufficient for the OWRB to satisfy its obligation to provide the public with adequate notice, Kemper alleges.

The Kiamichi Basin encompasses 1,821 square miles and “generally includes” LeFlore, Latimer, Pushmataha, Pittsburg, Atoka and Choctaw counties, and does not include McCurtain County, Kemper wrote. Therefore, the OWRB did not provide proper notice in Atoka and LeFlore counties.

Kemper also cites Rule 16, a “rule for district courts,” which stipulates that, “When a default judgment sought in any action against a party-defendant who was served solely by publication (i.e., upon whom no notice by mailing was effected), the judge shall conduct an inquiry … to determine judicially whether plaintiff … did make a diligent and meaningful search of all reasonably available sources at hand…”

“Reasonably available sources” include mailing addresses and whether records of the local county assessor, local county treasurer, local deed records and local probate records, if applicable, the rule specifies.

“If Courts recognize that the detailed requirements of Rule 16 remain necessary to ‘meet the minimum standards of state and federal due process,’ then it should be obvious that the publication-only requirements of OWRB regulations are constitutionally deficient as to notice” in the Kiamichi/Sardis water-use permit application case, Kemper alleges.

Dilution of Red River Has Not Been Considered

Another issue that has not been addressed in the ongoing litigation over the Kiamichi River and Sardis Lake is the potential impact that Oklahoma City’s water withdrawals could have on the salinity of the Red River.

The Red is ultra-salty on its path through most of southern Oklahoma. But as it continues downstream past Denison Dam it begins to get diluted with fresh water from creeks and the Kiamichi River, plus several fresh water sources in Arkansas. By the time the Red River reaches Louisiana, it is used to irrigate crops.

An official with the U.S. Geological Survey reported recently that an ongoing study of the Red River Basin does not include water quality. That study is focused just on water modeling and water use, the USGS official said.